German word: Hoffen

German example:

Ich hoffe, dass es dir gut geht.

English example:

I hope you are feeling well.

| ) |

masculine

|

neuter

|

feminine

| |

|---|---|---|---|

indefinite (a/an)

|

ein Mann

|

ein Mädchen

|

eine Frau

|

definite (the)

|

der Mann

|

das Mädchen

|

die Frau

|

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich bin | I am |

| du bist | you (singular informal) are |

| er/sie/es ist | he/she/it is |

| wir sind | we are |

| ihr seid | you (plural informal) are |

| sie sind | they are |

| Sie sind | you (formal) are |

English person

|

ending

|

German example

|

|---|---|---|

I

|

-e

|

ich trinke

|

you (singular informal)

|

-st

|

du trinkst

|

he/she/it

|

-t

|

er/sie/es trinkt

|

we

|

-en

|

wir trinken

|

you (plural informal)

|

-t

|

ihr trinkt

|

you (formal)

|

-en

|

Sie trinken

|

they

|

-en

|

sie trinken

|

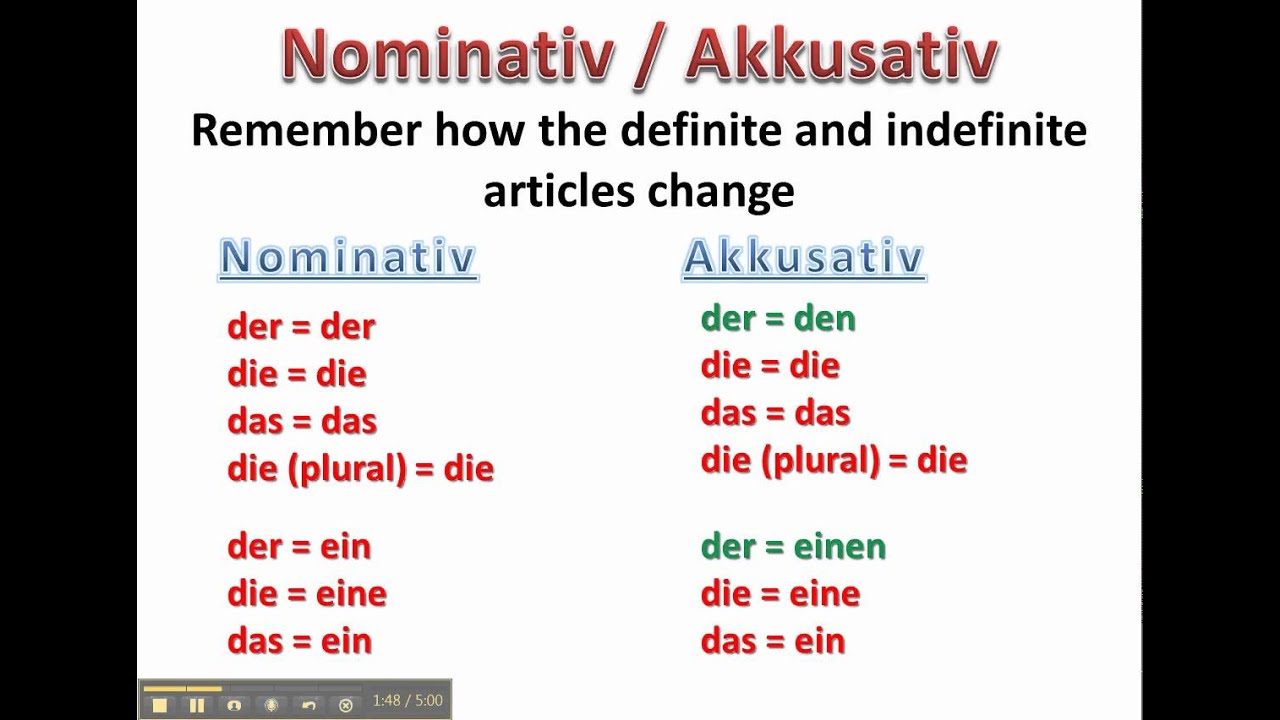

| Case | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | der | die | das | die |

| Accusative | den | die | das | die |

| Case | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | ein | eine | ein |

| Accusative | einen | eine | ein |

| German | English |

|---|---|

ich bin

|

I am

|

du bist

|

you (singular informal) are

|

er/sie/es ist

|

he/she/it is

|

wir sind

|

we are

|

ihr seid

|

you (plural informal) are

|

sie sind

|

they are

|

Sie sind

|

you (formal) are

|

| English person | ending | German example |

|---|---|---|

I

|

-e

|

ich esse

|

you (singular informal)

|

-st

|

du isst

|

he/she/it

|

-t

|

er/sie/es isst

|

we

|

-en

|

wir essen

|

you (plural informal)

|

-t

|

ihr esst

|

you (formal)

|

-en

|

Sie essen

|

they

|

-en

|

sie essen

|

| English person | ending | German example |

|---|---|---|

| I | -e |

ich habe

|

you (singular informal)

|

-st

|

du hast

|

he/she/it

|

-t

|

er/sie/es hat

|

we

|

-en

|

wir haben

|

you (plural informal)

|

-t

|

ihr habt

|

you (formal)

|

-en

|

Sie haben

|

they

|

-en

|

sie haben

|